Any number of reminiscences might carry this title. But for this essay I’m not relating a specific episode with a humorous ending or a personal insight. Instead, I’m sharing with you the blow-by-blow of a standard chore I performed time and time (and time) again while growing up on a farm in the late 60s, early 70s.

Imagine a late winter’s eve in rural southwest Missouri. The sun is setting on a day when the sun never pushed the temperature above 30 degrees; it is now quickly heading down toward 25 or lower. You’ve been back from school about an hour, time enough to change clothes and start the evening feeding routine on a hog farm that’s home to several hundred animals. The feeder pigs are on a concrete pad with automatic feeders and waterers, so today there’s nothing to do for them. But the breeding stock is sheltered here and there and has to be fed individually.

In the farrowing barn, the momma pigs have gotten their feed pellets mixed with bran, all portioned out using a coffee can. In the lots around the barn, you’ve also fed and checked the watering troughs in the pens holding sows in various late stages of gestation, waiting for their turn in the barn. Plus the two boars, individually housed far apart from one another.

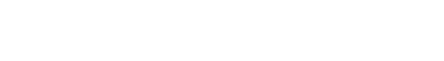

This picture from a vintage sales flyer is the exact automatic waterer that was lashed to a fence post in a far-off field.

This lamp was key to ensuring water continued to flow in subzero temps. It hung out inside the base of the waterer.

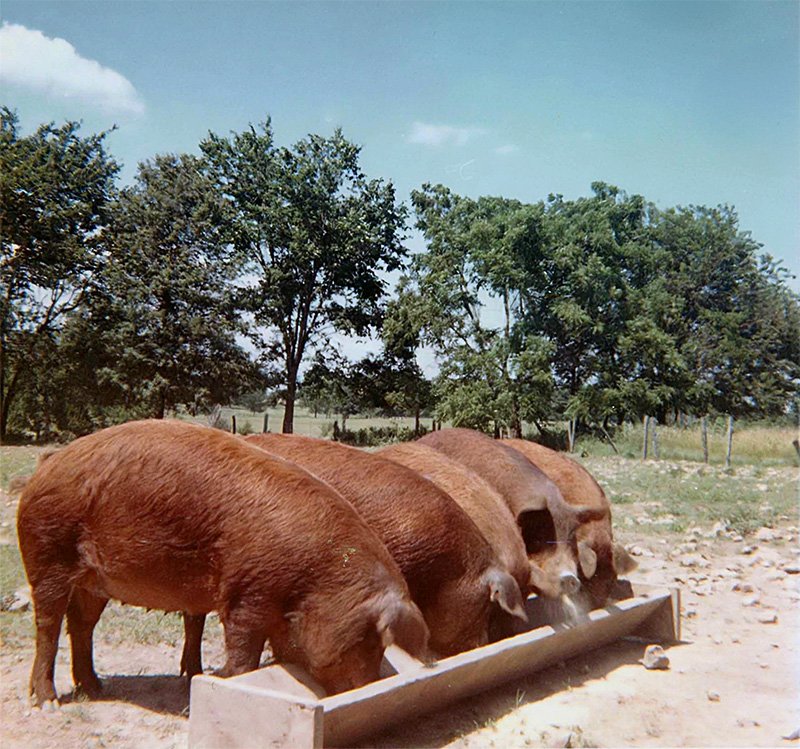

A barrel very much like this helped transport water summer and winter.

Now the Fun Begins

Now it’s time for the final chore: Hauling food, water, and straw to two separate pens of sows at the far end of the 40-acre farm. Unlike the barn animals, they get one feeding a day, so it can’t be missed just because it’s dark and your toes are already feeling like ice cubes.

First, beverages. It’s not so frigid that water’s going to go snap! and freeze on contact with the air. But it barely got to 30 degrees today, so the pond in field 1 is frozen over. Bring along the axe for that. In field 2, no pond, so it’s equipped with an automatic waterer that will need filling. You see here an illustration of the exact Pride of the Farm waterer in use. See the flap on the right side? Slide that up to get access to the inner chamber, where a kerosene lamp, of a type very much like the one pictured here, could keep the two water stations from freezing. It would have had a braided cloth wick that you could adjust with that little twisty knob. It ran on kerosene, a smoky apparatus. Filling the water required filling and transporting a repurposed 55-gallon steel drum, kinda like the one pictured.

Second, the main course. We made our own feed. Once or twice a week we’d pull the second of our tractors, a mid-sized Farmall tractor hooked to a portable feed mill, around to the homemade corn bin (or later, our own silo). As the corn was being ground into meal, in went a few scoops of vitamin/supplement stuff that smelt a bit like something dead (which it probably was). I scooped the feed into tall, 5-gallon buckets. Depending on how many mama pigs there were to feed, each lot might need two or more buckets. They were darned heavy when full.

Third, bedding. Gotta get up into the barn loft and chuck down two bales of straw, one for each lot.

Let’s Load Up

A much more modern — and clean! — version of our aging Case tractor. Closest I could find of this “tricycle” style.

I’d learned to drive on a limping Case tractor like the one here, only not so spiffy. The paint was faded; the exposed engine block was covered in a patina of old oil, looking somewhat like black mold. A tooth had been chipped off the reverse gear, so it clanged when backing up. And it was a much older model than this one. How can I tell? See that plate under the front grill? On ours, no plate; that’s where you inserted the crank to start the sucker. At the end of the day, I would make sure to park it right at the edge of a steep, three-foot incline. That way, I could get up in the seat, open the choke, push in the clutch with my left foot, and hang my right leg over the other tire guard and push on the tire tread mightily to coax the jalopy over the edge. Hopefully, pop the clutch to start the engine. If that didn’t work, I had to get the crank and give it a whirl. My dad had put the fear in me about using the crank, with his tales of how the kickback could break your arm if you weren’t careful to withdraw it quickly. I believed him. I never experienced the full kickback, but you could still feel the powerful surge when the motor kicked in.

Tractor started, I hooked it to a four-wheeled, flatbed trailer. My dad had gotten a clackety metal frame (or maybe it was already here on the farm, abandoned when we moved in), and he rebuilt it by adding a plywood bed. It clattered and clanked, but served the purpose. First, I hefted the empty barrel up onto the trailer, laying it on its side, pushing it up against the front railing, and then snugging it tight by wedging a two-by-four against the other side. The spigot had to be on the bottom, the bung that closed the barrel on the top. If I’d done my job and drained it well the night before, there was no water frozen in the spigot. If not, or if it froze on the way to the back fields, I always kept a few scraps of newspaper or flyers and matches (which come in handy later) to burn under the spigot to thaw it out. Even if the bung was frozen in its threads, a whack with a hammer or butt-end of a screwdriver would usually free it up.

While the barrel was filling with a hose, I’d load the feed buckets, axe, and an empty water bucket. Toss the bales of straw on. Once the barrel was filled, I drained the hose by unscrewing it from the faucet, holding up the coupling end shoulder high, and walking the length of the hose to drain the water. Couldn’t have it frozen for tomorrow’s chores.

And We’re Off …

You’re tootling down a dirt lane toward field 1. Can’t hotrod, or else you’d spill the feed buckets.

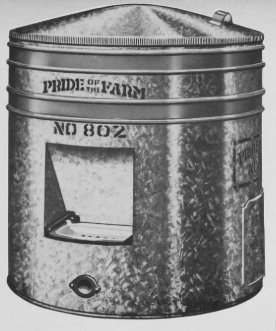

The only real photo available from the farm. Just imagine the trough turned upside down, frozen to the ground.

At field 1, the first challenge. Notice the picture of the homemade feed trough, with momma pigs peacefully munching breakfast (the only picture I’ve got from our farm for this story; phones rigged out with cameras were about three decades in the future). In good weather like that, before you could dispense the feed you’d usually still have to turn it upright. After finishing their cornmeal feast, the ladies would root around in the trough and often, in so doing, they’d turn it over. Ah, but it’s winter. Sometimes, the overturned trough was also covered in snow that had to be shook out if the trough was upright or dusted off if the trough was upside down. More frequently, it’s also at least frozen to the ground.

Now, you can’t just wade in amongst the crowd of hungry mommas and fix up the trough. They’re circling all around you, getting in the way, frustrating your attempts to bend over and lift the trough up while they’re nuzzling it and they’re rubbing up against you. So, you had to walk casually down the fence line, while they followed along, noisily whining and grunting. Then you’d break back quickly, jump the fence, reach the trough, maybe give it a kick to loosen it from the frozen ground, and then turn it over before the girls arrived to stick their noses in, expecting dinner. If there were two troughs, hopefully they were far enough apart that, while the ladies inspected the one you’d just overturned, you could spring free and fix up the other.

Next, the same fake-and-run routine. Taking one of the heavy buckets, walking down the fence, then breaking back to jump over and get to the trough before they did, trying as best you could to shake the feed evenly down the length of the trough so everyone had a fair chance of getting enough dinner. Not an easy sprint lugging that leaden bucket of feed.

In field 1, the watering task required chopping ice on the pond. Some folks might just whack around to create some open but slushy water. Not me. It felt unkind to make the animals deal with the slush. I carefully cut a square of ice three or four feet wide so that several mommas could drink, side by side, from an unobstructed patch of water. Then I’d use the axe to either lift the square up on top of the ice and slide it toward the center (where other blocks were parked from previous days), or push it below the lip of the ice and send it gliding under the ice.

Lugging the bale of straw to their little lean-to house (like the one pictured in this tale, but three-sided) was the easiest of the tasks. Lift the bale by one of its two lengths of twine, knee in the middle, break it apart. Scatter. Done.

Now on to field 2, further away. It’s close to full-on dark by now, and the chill is really settling in. Same procedure to do the feeding and dispense the straw. But … the waterer.

Everything Before this Was the Easy Part

Now we come to the experience I actually set out to tell you about. All the previous stuff? You had to know the details that lead up to this moment, so you can appreciate that servicing the waterer was a whole ’nother challenge.

Pull off the lid of the waterer and, bucket by bucket, empty the maybe 45 gallons (you couldn’t fill it to the top) from the barrel into the waterer. Make sure to get all the water by finally hanging the bucket on the spigot and, stretching out both arms to clasp either end of the barrel, tilt it forward to make sure every drop dribbles out. Can’t have it freezing in the barrel or clogging the spigot.

Now it’s back into the pen, on your knees by the side of the waterer. Try to get enough purchase with your fingers to slide that metal flap up to reveal the kerosene lamp inside. Sometimes the kerosene lamp is still flickering. Sometimes not. Regardless, you have to remove the lamp, check the kerosene, and top it off if necessary. The wick has burned down, so you’ve got to twist a length of wick up to pull off the ashes to reveal fresh, unburnt cloth. The wick and ashes are saturated with kerosene, so your gloves are icky with what is essentially oil-based black paint; it travels through the gloves to your fingers, making post-chore washup with Lava soap a requirement. Twist the wick back down to about the right level to hopefully last another 24 hours. (Trial and error over many weeks.) Lamp goes back in the middle of the waterer (you have to keep the whole tank warm enough, not just the two watering stations).

Out come the matches. This is not a job you can do with your gloves on. Bending over, you strike a match and reach inside, holding the match against the wick until it flickers and you’re sure it’s lit. If it’s a calm night, it could be that simple. But even a small wind turns this into a Sisyphean task. Just keeping the flickering match protected long enough to get it close to the wick is drama enough, but holding it till the wick is lit, still more drama as the flame draws closer to your fingers. Try to use your body to block the wind. Pull the metal side flap down to block some of the wind, so you’ve got just enough room to get your hands in. Many matches, much frustration. Finally, wick lit, you’re down on your knees and elbows as you lower the flap, peeking through as you slide down the flap, making sure the wick’s still burning.

Filling the waterer and servicing the lamp has taken time. Time enough for momma pigs to have finished dinner and want a drink. While you’re doing this they’re circling around you, whining and complaining. Nudging you. They’re gentle animals, so you’ve got nothing to worry about. (Well, one time I think an awkward toss of someone’s head got a tooth snagged in a pocket of my jeans, ripping the pocket right off.) Sometimes you pause a second to scratch one of the more amiable ladies behind an ear (they love this). Sometimes you have to give one a tap on the butt to move out of the way.

No, You’re Not Done Yet

Those two watering stations that give the girls access to the water? The sows are usually drinking right after eating, so a lot of cornmeal leavings wash out of their mouths. Every now and then you gotta clean the sludge out. And that’s a job you can really only do by hand, again sans gloves. You lift the metal grate inside the watering hole, pull off a glove, reach in and scoop out the sludge. Oh, that’s cold work. And the smell will remind you of, maybe, a rancid sponge. Well, worse. It’s the kind of smell that lingers on your skin. More scrubbing with Lava awaits at home.

But now, at least, you’re truly done. Hands given a quick rinse with a few drops of left-over bucket water. Dried on your jeans. Gloves back on. Trailer loaded up. You can now tootle back to the barn a little faster, but still not hot-rodding or you’ll shake the empty barrel and buckets right off the trailer. (You can guess how I know this will happen.)

Back at the barn, stow the barrel upright, spigot up, so any drops of water freeze on the bottom. Buckets go in the barn. Park the tractor at the top of that incline to enable tomorrow’s rolling start. The day is done.

Now You’re Asking … Really?

Was all this really, really what it was like every day? No, not every day. On non-freezing days you didn’t have to deal with the kerosene lamp or chop pond ice. Then again, on rainy days you’d have to slop through mud to overturn the troughs and outrun the ladies. Summer days, when the sun was still blazing in the late afternoon, it was a sweaty job. But those dark, frigid, winter nights, those are what I remember the most.

And now you’re also asking again … really? This is really, really why I’m not a farmer? OK, you’ve got me. Honestly, I admit I just wasn’t cut out for it. Other types of work excited me. I never once considered making farm work my life’s profession.

Did I hate it? No, never. It was simply work that had to be done to feed some animals that wouldn’t eat otherwise. It was difficult, and in its difficulty it gave me some satisfaction that I was able to do it day in, day out, with some degree of proficiency. In fact, a half century later I’m glad to have had the experience and glad to have a story like this to pass along to family and friends and anyone bored enough to spend the time reading or listening. And the willingness to stick to unpleasant jobs that had to be done served me well in other professions I tackled beyond the farm.

So that’s why there’s more honesty in the subtitle about farm work not being as romantic as non-farmers often think it is. My experience on the farm rid me of any fantasies about being close to nature, working the soil … all those Hallmark movie cliches. It’s hard work, all day, every day. It wasn’t for me. But I’m glad that others embrace it, and I respect them mightily for their choice.