How did a Missouri farm kid with a degree in Writing and English wind up, 40+ years on, running “marketing operations” for a global tech firm? I did not enter, or exit, college with a specific future in mind. From my first career stepping stone to the last, I usually let serendipity lead me to the next interesting thing to learn, which in turn led me to the next interesting thing to do.

Herewith, a step-by-halting-step account of what I learned along the way and how it all added up, eventually, to my best and last jobs. I’ve omitted hundreds of details that I may flesh out later in separate posts. For now, I keep it as terse as possible, but I’ve got several decades to cover. You can skip to the end for final thoughts.

1972. Editor, Wildcat Chatter, Rogersville, Mo.

Remington Manual Typewriter.

For the student newspaper of Logan-Rogersville High School (a stone’s throw southeast of Springfield), I typed copy on a manual Remington. I “justified” columns by typing twice: once to see how many blank spaces were needed to the end of the line, then again to insert that many spaces between words to pad. Already, I couldn’t contain my more anal tendencies.

1976. Editor, Queen City Chess Bulletin, Springfield, Mo.

Smith-Corona Electric Typewriter. Press-on Headlines.

My first typewriter was a high-tech miracle, an electric Smith-Corona that my Grandmother Elley gave me for high school graduation. The perfect gift for a prospective English and Writing major.

During my university days, I also used it to type up each page of this chess newsletter, then embellished the layouts with press-on headlines and diagrams. This gave me entrée to The Chess Journalist newsletter, which would change my life a few years hence. By the final issues, fellow woodpushers were contributing pages as well.

1977. Reporter, then Editor of The Standard, Springfield, Mo.

Paste-up with Cold Type. Hot Waxer. X-Acto Knife. Proportion Scale.

Preparing the student newspaper of Southwest Missouri State University (now Missouri State) was not a far leap from the chess newsletter. We submitted typed copy to the printshop, got back typeset galleys, and sliced these into narrow columns with an X-Acto knife. You shoved a small block of gummy wax into the top of the black waxer, secured it with that red stopper, then plugged it in. A few minutes later, you could roll melted wax over the backside of your type and press the type down (positioning it EXACTLY) into place on layout sheets.

With the proportion scale, you could measure the width of a photo, the width of the place in the layout where it was to appear, and then line up those two numbers on the inner and outer scales. Presto, you had the reduction percentage and the height of the other dimension.

1978. Advertising Writer, Bass Pro Shops, Springfield, Mo.

Compugraphic Typesetter. More Cold Type Paste-Up.

I’ve already shared how I was lured to Bass Pro. Though hired as a writer, my typing skills and understanding of basic paste-up from my college days came in handy as a backup typesetter in the art department.

Inside this early Compugraphic phototypesetter was a spinning drum, upon which a filmstrip containing the font images was stretched. As you finished typing the number of characters the machine felt would fit on a line, boom! Light strobed through the filmstrip, letter by letter, blip! blip! blip! blip!, to expose photosensitive paper. You then fed the rolled photo paper through a developer and let dry to get your galley. This beauty had no memory. So care was needed as you sensed you had entered enough characters for a line, to keep it from hyphenating a word such as: br-ing.

1978. Copyeditor, Springfield News-Leader, Springfield, Mo.

Computer “Dumb Terminal” for Editing Copy and Headlines.

The “slot man” (often a woman, actually) assigned stories to the copyeditors sitting around the circular copy desk. It was our job to trim the stories to a specific line count and to write headlines to a specific character count.

The terminal’s display showed a few lines of monospaced text. After surfing the cursor around the display to whack out what you thought must be enough text, and wrote the headline, you had to issue what I recall as an “H&J” command (hyphenate and justify) to redisplay the story to see how close you were. You worked fast, as pages had to flow on schedule so the backshop could do the layouts (which still looked a lot like the college newspaper).

1979. Assistant Editor, then Editor, Chess Life Magazine, US Chess, New Windsor, NY

Compugraphic Editwriter 7500. Years of X-Acto Knives and Hot Wax Paste-Up.

The briefest “help wanted” blurb in the aforementioned Chess Journalist newsletter landed me this job. The EditWriter 7500, the big brother of the Bass Pro rig, still wasn’t WYSIWYG, so you had to visualize as you typed arcane formatting codes to change type specs.

An early learning: “If you can think of an idea, you do make it happen.” We needed dozens and dozens of chessboard diagrams in each issue. I was the chief architect of the layout of the pieces on the filmstrip that held the imprint of the pieces and squares.

The essential tech breakthrough: Text was stored on 8-inch floppies (which really were floppy). So you could store a story and return later to enter edits. I created Compugraphic “templates” by storing the series of keystrokes needed for repetitive font changes, which could then be replayed to save time – a precursor to programming.

1985. Publications Director, US Chess, New Windsor, NY

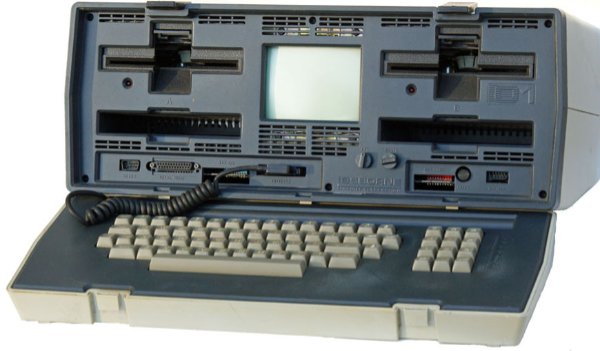

Osborne 1 Computer. PC Jr. Wordstar. Macintosh 512K and ReadySetGo.

I actually wrote a draft of a guide for chess teachers on an Osborne 1, the first portable (though some more accurately dubbed it the first draggable) computer. The transition to Wordstar was smooth, as the awkward text commands for styling type were very much like typing font changes on the Compugraphic.

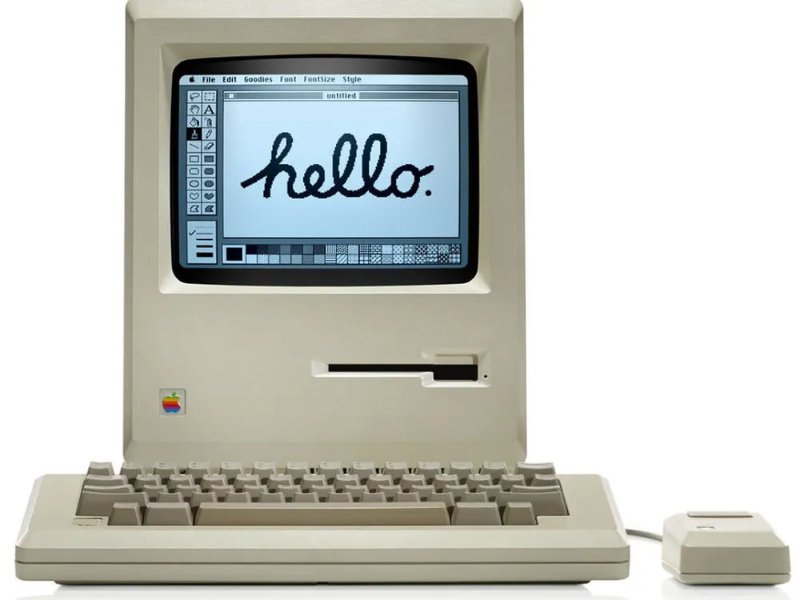

For the launch of a kids’ magazine, the consultants could never get Ventura Publisher on a PC to print. I hauled my personal, prized Mac 512K and an early layout program, ReadySetGo, into the office to save the day.

I’d gotten a great trade-in deal for my Apple IIe. The big decision had been: Mac 128K or 512K? (A lesson for the ages: more is better.) The 512K lasted me several years as various upgrades turned it into the classic Hackintosh.

1987. Technical Editor, Sykes Enterprises, San Jose, Calif.

IBM 3270 Dumb Terminal and GML. Macintosh and Turbo Pascal.

I moved cross country to California to be with family. The tech-nerd in me began to blossom as I joined a company that did contract writing for IBM. We worked on IBM 3270s, a non-WYSIWYG dumb terminal where you still used a keypad to push the cursor around the screen.

Here was something new: To style type, you used Generalized Markup Language (GML) by surrounding items like headlines with <h1> and </h1> tags. No arcane keystrokes, something intuitive. Little did I know how fateful this skill would be for future jobs.

My copyediting chores, however, were still straight out of the 70s, using a red pen and standard copyediting marks on printed copies of my colleagues’ drafts.

To feel confident editing a Pascal programming manual, I learned some rudimentary scripting skills using Turbo Pascal on my Mac.

1991. Senior Technical Editor, Software Publishing, Santa Clara, CA

Tower PCs and the Advent of Microsoft Office Apps.

This was the beginning era of tower PCs running early versions of Windows, plus the occasional Mac. Microsoft Word was becoming the gold standard, and it was packaged as something called “Office” that threw in Excel and PowerPoint. The so-called “Suite Wars” between Microsoft, Borland, and Lotus drove companies like SPC out of business.

On the positive side: WYSIWYG displays and mice finally became standard kit.

However, I was still hand editing a lot of printouts. Writers still had the final say about how much of my scribbles to embrace. But Word’s change-tracking features were about to shift the balance of power between writer and editor.

1994. Consulting, Silicon Valley

Windows and Mac PCs. Photoshop and Macromedia Director. Scripting in WordBasic.

Oh, the fun I had. Just a few samples …

For San Jose’s Cinequest Film Festival I volunteered to create the print catalog on QuarkExpress on the Mac. I did the interior editorial layouts and most of the advertising pages, and the printer knitted it all together. I also volunteered to do the final production for a newspaper for a homeless charity in San Jose.

The Pascal background helped me learn enough WordBasic scripting to programmatically untangle badly bungled online help systems written in Rich Text Format (RTF).

Those rudimentary programming skills, supplemented by classes in Photoshop, plus Macromedia Director and its programming language, Lingo, enabled me to bluff my way into a contract with Macromedia Press, updating their official Macromedia 6 and Lingo Authorized tome. (Google searches still insist, three decades later, that this is the most important thing I’ve ever done.) Most exciting and foreshadowing? For that book I wrote a new chapter on how to deploy Director-created animations on something called “The Web.” The GML experience made learning the necessary HTML a breeze.

One chief qualification for many contracts? I was something of an expert in cross-platform content at a time when Macs and PCs were not on the friendliest of terms. The Macromedia writing, for example, had to be done with screenshots on both operating systems. Software and hardware were expensive. So when the phone stopped ringing for Mac projects in the mid-1990s, I breathed a sigh of relief.

1997. Training Writer, Web Developer, OOCL, San Jose, CA

Building on HTML Skills.

I got an intensive education in PowerPoint by crafting training decks for the completely rewritten voyage tracking software of this container ship behemoth. They had seen Y2K coming years early and decided to be prepared.

My HTML skills got me invited to projects for their internet and intranet sites. I decided this web stuff was the career I never knew I wanted … until now.

But first, I decided … I needed to work for a startup.

1998. Web Site Manager, NetIQ (now CyberRes), San Jose, CA

Active Server Pages and VBScript. Lots more HTML.

A “friend of a friend” connection landed me a job with a fast-growing startup. Hired as a writer, I insinuated myself onto the web team by volunteering to translate support engineer’s notes into consumable website knowledge base articles. I took a peek under the covers. Holy moly! Something called Active Server Pages and VBScript, a close cousin of the Word Basic I was already familiar with. Page templates were handcoded in a blend of VBScript and HTML (like you see here). The inline styling required the type of attention to detail I’d acquired visualizing in non-WSYIWYG displays and typing arcane font changes on the Compugraphic and Wordstar. Something called Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) seemed like a handy new innovation.

By the end of my tenure at this fast-growing startup, I had fully made the transition to marketing (who would have thought!) and was managing a team of web producers and developers (up to 18 at one point).

2004. From Product Marketing Manager to Senior Director of Marketing Operations, Centrify (now Delinea), Sunnyvale, CA

Web Technology. Microsoft Office. Marketo and Salesforce.

As employee 16, I grew from “all things marketing” to eventually managing the marketing tech (martech) stack. I leaned on all my previous skills: writing to craft white papers, data sheets, and more; web dev to create the website; and general nerdiness to bluff my way into becoming an admin for enterprise software like Marketo (to collect and nurture sales leads) and Salesforce (to present the most promising leads to Sales and keep an eye on them … on Sales, not the leads).

This felt like where I always needed to be, but of course none of this existed when I’d graduated from SMSU some three decades earlier. I started in an intensely hands-on role, but 13 years later I was transitioning from “the one who gets it done” to “the one who manages how it’s done.”

2018. Director, Marketing Operations, Arm (San Jose, CA, and Cambridge, UK)

More Marketo and Salesforce. A Tower of Martech Babble.

I leave behind web dev to focus solely on managing the global martech environment for a microprocessor giant that was reinventing itself. I’m still hands on with tech like Marketo and Salesforce, but there is also a cacophony of overlapping services like Microsoft Dynamics.

My communication skills and original DNA for “explaining stuff” (not to mention facility with PowerPoint) are essential for evangelizing modernization practices.

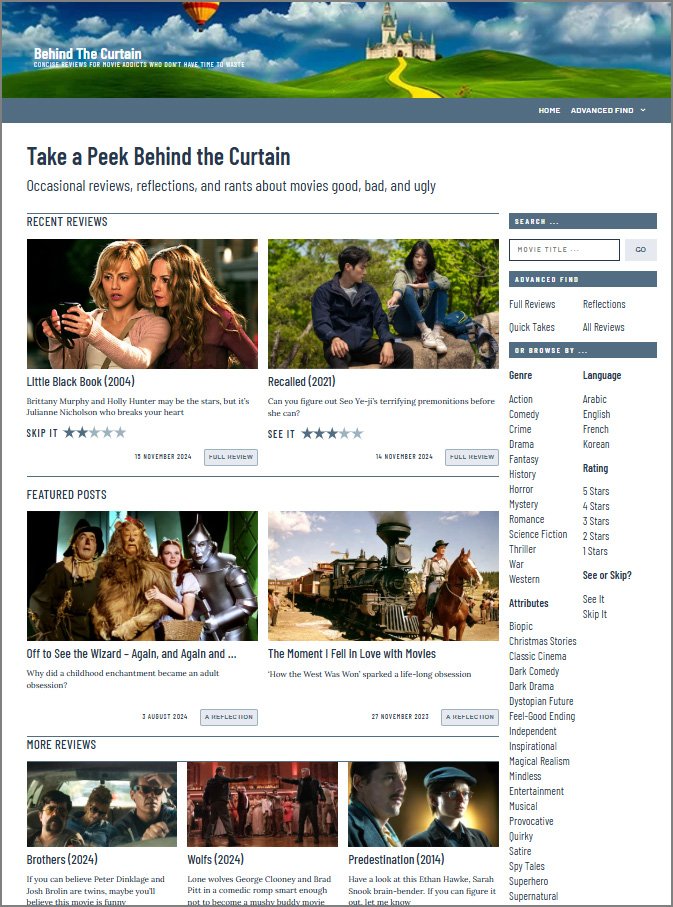

2022. The Man Behind the Curtain, Goodyear, AZ

WordPress. Naps. Random Writing.

As Arm headed to re-IPO, it needed to drastically trim expenses (AKA: people). I volunteered for an attractive layoff package, easing my transition to retirement. What’s next? Naps. And hobbies!

In 1996 I’d registered the domain behindthecurtain.com. It went through a few iterations, but once freed from indentured tech servitude I relaunched it as an unambitious movie review hobby on WordPress. Here at frankelley.com, I’m sharing personal reminiscences and sketchy career musings (I’m reluctant to call it advice).

Is There Any Point to All This?

At graduation in 1978 in Missouri, I was not thinking in terms of having a “career.” I certainly didn’t have in mind to become director of marketing operations in California for a global, UK-headquartered microprocessor giant – a company that would not even be founded for another decade. The web was a dream. People I’d wind up managing weren’t born yet. There’s no way I could have anticipated what my best and most satisfying jobs, toward the end of my non-career, would look like or where they’d be located.

But every new skill I learned, or existing skill I honed, from teenager to retiree, built on previous learnings and brought me great satisfaction. As I skipped from one job to the next, each new experience brought me one step closer to the best roles I’d enjoy at the end of my serendipitous path through work life: justifying typed columns on a manual typewriter; laying out print projects using X-Acto knives and hotwax; transitioning to PC-based software to do the same type of layouts digitally; hand-programming web sites; configuring the cloud-based marketing and sales applications that caught the data downstream of those websites; architecting program flows and helping colleagues visualize and appreciate how those processes were built to serve their needs. Each new skill, built on top of previous experiences, led to opportunities that I could have never anticipated because the future opportunities didn’t exist at the time I was learning those more basic skills. The only other thing I needed: the gumption to make the leap and believe I could succeed at that next new job.

My final advice will sound familiar: Be willing to invest in yourself, even if you don’t see an immediate payback. What I hope I’ve added to this rather commonplace observation is a blow-by-blow, real-life case study proving that it actually works.

As I look back over the path I’ve traveled – constantly learning new things, taking leaps into roles I barely felt myself qualified for – I can feel proud (and, granted, a bit fortunate) of how far I was able to go.

Afternotes, and a Final Thought

I’ve tried to condense, and simplify, 40-plus years of experience. I’ve recounted things to the best of my memory, and for those few of you who were also there, and also here reading this, I hope I’ve gotten it right in spirit if not with 100% fidelity.

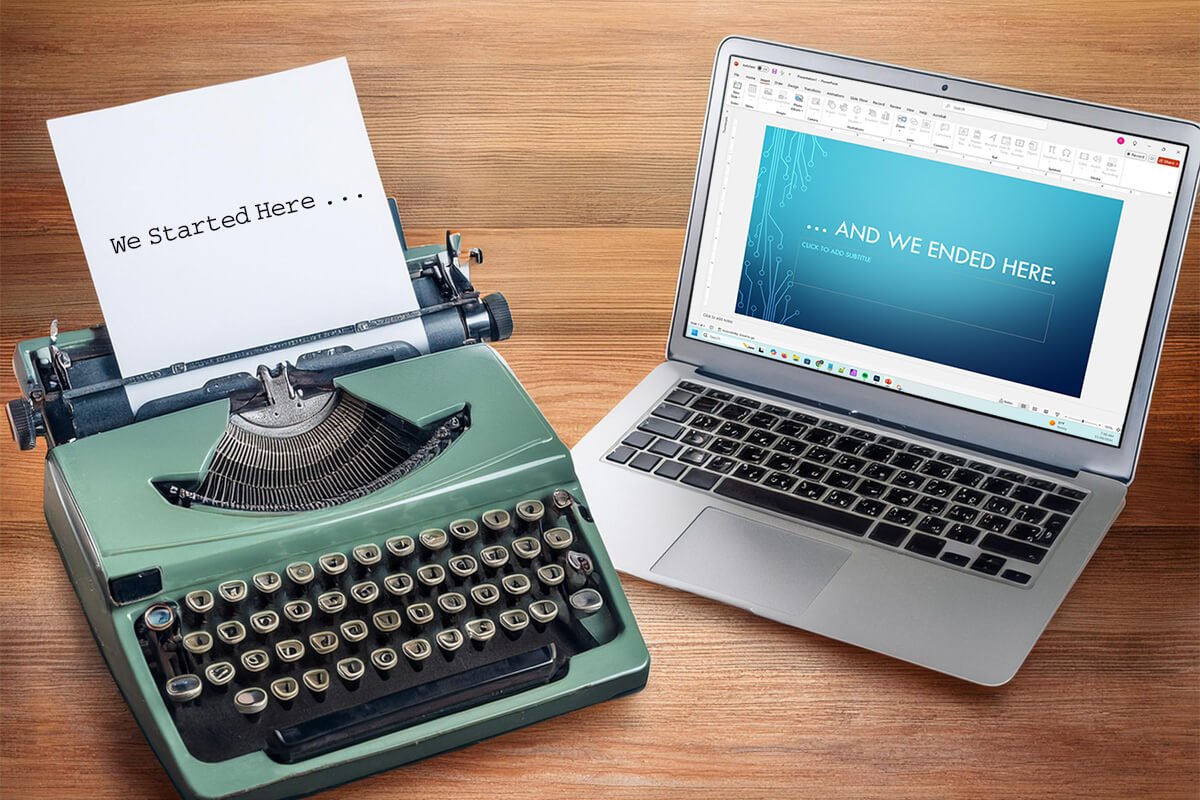

I’ve been lazy with image credits this time, but most are open source items borrowed from Wikipedia or non-copyrighted resources. Time allowing, I’ll continue refining text and presentation here. I just had to stop and move on for a while to clear my head.

The featured image at the top is my amateurishly AI-generated composite from Photoshop. The idea struck me while scrolling through all the images I’d collected: While many things have fundamentally changed in my work experience, one thing hasn’t been re-invented in all these years: keyboards. How many millions of characters have I typed in this lifetime? Unknowable. I reluctantly took my Mom’s advice and signed up for that typing class in high school. Mom knew best. In college, upon hearing one semester’s menu of Shakespeare and Linguistics, she’d nicely commented, “Too bad you aren’t interested in computers.” She’s gotten that right, too.